The Sudarium of Oviedo

Many people concluded that the Shroud of Turin must be a clever forgery once the carbon 14 dating test results of 1988 were announced. Those results apparently established a date of origin for the material ranging between 1260 and 1390 A. D.

The three laboratories selected to perform the tests had impeccable reputations. They worked independently, yet achieved remarkably similar results — all three labs declared the shroud had a medieval origin, more than a thousand years after the death of the Christ. Assuming their work was stellar and the results were accurate, the Shroud could not possibly have been used to cover the body of Jesus after the crucifixion. So why has it been preserved and continues to be venerated, if the shroud is nothing but a fake? And why have people continued to study a forged relic?

These and several other questions came to mind while watching the History Channel special (link to full program here) titled “The Real Face of Jesus”:

- Is it possible to still believe the shroud could be real, given the results of carbon dating experiments performed in 1988?

- Should the veracity of the scientists and the results of the tests be trusted?

- If the Shroud really wrapped the body of a dead human being, was that man the crucified Christ?

- If the Shroud is genuine, can it be used to somehow determine what Jesus looked like?

The first three questions enumerated above will be answered in this article, and the fourth question will be addressed in the fourth and final installment of this series.

In my personal opinion, the integrity nor reputations of the scientists who performed the carbon dating tests should be impugned, nor should their motives be questioned. Any impartial observer should realize that their efforts were sincere and the results of their experiments were accurate for the sample tested. The problem with the carbon dating turned out to be that the sample taken from the shroud as part of STURP came from a contaminated section of the shroud. Those carbon dating results were first challenged in a 2000 paper published by a couple of amateur investigators named Sue Benford and Joseph Marino. Benford and Marino had asserted that the sample tested had been contaminated when repairs were made in the past.

Their claims infuriated a member of the original STURP team named Ray Rogers. Rogers carefully examined residual material he kept that had been left over from the original sample used in the carbon dating tests. It was a known fact that the shroud had once been damaged by fire. Bedford and Marino theorized that repairs to the original material had been made on the very section of the shroud from which the sample to be tested was taken.

Determined to prove them wrong, Rogers re-examined his sample only to discover cotton fibers that weren’t consistent with the rest of the fabric, which was a linen weave. The result of Rogers’s investigation inspired by Benford and Marino turned into the 2002 paper titled “Scientific Method Applied to the Shroud of Turin.”

In his paper, Rogers invalidated the carbon dating test results from 1988 and even announced that he was close to proving the shroud was genuine — a point I would contend is impossible, given a lack of DNA evidence.

Chemist Robert Villareal of the Los Alamos National Laboratory said this about the carbon dating results controversy:

The age-dating process failed to recognize one of the first rules of analytical chemistry that any sample taken for characterization of an area or population must necessarily be representative of the whole. The part must be representative of the whole. Our analyses of the three thread samples taken from the Raes and C-14 sampling corner showed that this was not the case.

However, even before Rogers published his 2002 paper refuting the carbon dating test results for the Shroud, there were several more excellent reasons for harboring lingering questions about the accuracy of the test results.

For example, a copy of the Shroud had been painted in 1516. The copy clearly showed the “L” shaped burn marks from fire damage, but not the larger scorch marks that also can be seen on the Shroud today. Therefore, prior to 1516, the Shroud must have been damaged by fire, even though a second fire is known to have occurred in 1532. The painted copy was obviously made before the second fire created the scorch marks. But there is much better corroborating evidence for the shroud that allowed the skeptical mind to wonder about the validity of the carbon dating test results.

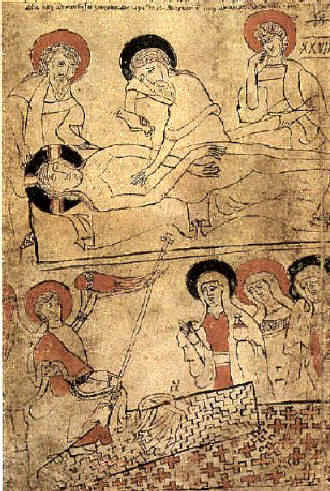

Interestingly, a relatively obscure book known as the Hungarian Pray Manuscript has an intriguing, very unique image depicted on its cover. It clearly shows the same distinctive herringbone weave pattern found on the actual Shroud of Turin, and even shows the L-shaped burn marks (but not the scorch marks, which is an important point to note.)

Interestingly, a relatively obscure book known as the Hungarian Pray Manuscript has an intriguing, very unique image depicted on its cover. It clearly shows the same distinctive herringbone weave pattern found on the actual Shroud of Turin, and even shows the L-shaped burn marks (but not the scorch marks, which is an important point to note.)

Documentation proves that the Hungarian Pray Manuscript existed as early as 1192-1195 A.D. — in other words, more than half a century prior to the earliest date estimate for the Shroud that was produced by carbon dating tests. That fact alone could only mean one of two things — either the current Shroud is an exact duplicate of material that existed prior to 1260 A.D., or somehow, the carbon dating test results had to have been wrong. However, the Hungarian Pray Manuscript is not even the oldest relic with a direct connection to the Shroud of Turin that called the carbon dating results into question.

The history of a second corroborating relic known as the Sudarium of Oviedo dates to at least 614 A.D. The Sudarium is a piece of cloth saturated with human blood that’s about the size of a dish towel. It is believed to have been used to clean the worst of the blood from the face of Jesus and cover his face, as his body was prepared for burial. Expert analysts have claimed that the bloodstains on the Sudarium perfectly match the blood patterns on the Shroud.

Furthermore, pollen evidence found on both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo match a flowering thorn known to only grow within a fifty mile radius of Jerusalem, which strongly suggests that both pieces of material were in Israel at one time. This pollen evidence establishes a very credible second link between the Shroud and the Sudarium that is unrelated to the blood evidence.

Does the Shroud of Turin prove Jesus was resurrected? Or does it only prove that a man crucified in a manner matching the biblical descriptions was wrapped in it and buried somewhere in Israel, within 50 miles of Jerusalem?

For skeptics and believers alike, the truth will always rely on an element of faith. If one doesn’t believe in the crucifixion and the resurrection, simply pointing out that without the DNA of Jesus to compare to the blood on these relics (assuming it hasn’t already deteriorated to the point where analysis cannot determine an exact match) there is no proof, and therefore no reason to believe as fact that Jesus really was the promised Jewish Messiah.

Likewise, Christians can take comfort from the knowledge that the carbon test results were proved wrong, and the Shroud absolutely could be genuine. The Shroud was almost certainly not forged between 1260 and 1390 A.D. Quite frankly, there isn’t a forger in the world who would have thought of faking that pollen evidence.

At this point, proposing that the Shroud of Turin was the product of a deliberate and malicious intent to deceive by some master forger takes more than faith; it requires a willing suspension of disbelief.

And there is still more to be learned about this crucified man by studying the Shroud of Turin.

Speak Your Mind