Michael Shermer

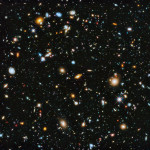

How would you describe outer space?

Do you think you could draw a picture of deep space that someone else would recognize for what it represented? What would you draw?

I have a confession to make: I usually enjoy the writing of famous skeptic Michael Shermer, and personally think he is an excellent author. In fact, I even bought the hardcover copy of his book Why People Believe Weird Things from the Roswell Public Library.

Literally, I had some difficulty putting that book down when I was actively reading it a few years ago.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I confess that I felt compelled to replace the original library copy because I accidentally got ketchup stains on a page and didn’t want to give them back a book that I’d damaged. Otherwise, I probably would have settled for buying the more economically priced paperback copy to add to my book collection.

I’ve admired the work of Mr. Shermer for some time. I even thought his guest appearance on Mr. Deity was hilarious, albeit in a somewhat sacrilegious sort of way.

Probably the most famous skeptic in the world today, Mr. Shermer was the founding publisher of both Skeptic magazine and founder of the Skeptics Society. Interestingly, the word “skeptic” has been defined two different ways in the dictionary:

Using those definitions as my standard, I would think that I should qualify for membership in Mr. Shermer’s club of skeptics, but I doubt that I’ll be welcomed in with open arms.

Personally, I think a certain degree of skepticism is healthy. Imagine my surprise to learn that I’m perhaps even more consistent in my skepticism than Mr. Shermer.

For example, I still have my doubts about “politically incorrect” things like global warming, and that the theory of evolution presents a rational belief explaining how monkeys can shape-shift into men, simply if given enough Deep Time for this amazing metamorphosis to occur. However, Mr. Shermer believes in both global warming and the theory of evolution, with a remarkable lack of curiosity in regard to the evidence allegedly supporting those theories.

It seems Mr. Shermer’s criteria requires that the skeptical person must also be an atheist in order to legitimately be called a skeptic. I’ve discovered over time that atheists seem to be quite eager to challenge my beliefs no matter what evidence is offered, but none of them are willing to equally apply skepticism to his or her own beliefs.

There is no balance. That’s not honest. That’s horribly biased skepticism.

The alternative to true skepticism is gullibility. The more preposterous a claim appears on the surface, the more critical it becomes to remain as skeptical as possible, until the evidence that substantiates the claim simply overwhelms you.

That’s much easier to do when applied to possibilities that you already doubt, and becomes infinitely more difficult to accomplish when applied to things you actually believe to be true.

It isn’t particularly easy for me to admit that my quest for truth has led me to believe some rather incredible scientific evidence exists that suggests reincarnation is actually possible, because that evidence conflicts with my Christian worldview, to at least some extent.

I would be dishonest if I denied that I’ve seen solid scientific evidence for reincarnation, because in fact, I have seen that evidence. Christianity doesn’t even address the issue, so I don’t know what to make of this evidence to which I refer.

I also know that my pastor isn’t exactly comfortable with the idea of reincarnation, but what can I say? It certainly isn’t required for me to like the concept of reincarnation in order to believe the evidence is credible, and it would be intellectually dishonest to ignore the evidence and pretend it doesn’t exist.

My point here is this: once someone makes a claim of possessing evidence, as skeptics we have an epistemic duty to investigate those claims, rather than summarily dismissing them.

In my book Counterargument for God I suggested that everyone consider themselves agnostic because there is tremendous difference between claiming to know something is true and being able to prove it.

I offered that we may characterize ourselves as atheist-agnostic, theist-agnostic, or apathetic-agnostic,depending on our current worldview

Once upon a time, I was an apathetic agnostic, on the brink of becoming an atheist. I considered the concept of supernatural intelligence to be about as preposterous as any other professed atheist would. Because I lacked paranormal experience, I assumed that ghosts were no more real than Casper, the cartoon character.

Then a friend of mine claimed his house was haunted after I witnessed a supernatural phenomena. At first I didn’t believe him, of course.

But then over time, I experienced multiple examples of inexplicable phenomena that were irrational by any stretch of the imagination — phenomena caused by some sort of an invisible force, and not once or twice, but dozens, if not hundreds of times. Light switches would toggle themselves as I watched. Keys would disappear and reappear in the exact place last seen. The motion sensors in the burglar alarms would get triggered by nothing.

It got to the point where further denial would be dishonest, silliness born of cowardice in the fear of what others might say about that admission.

My skepticism was only slightly diminished by the first occurrence, because I was fairly sure what I had seen had to have been a trick, because I believed ghosts was irrational. Also my friend laughed about the incident, making me even more suspicious.

After a while, so many inexplicable occurrences had happened that I got to the point I accepted that ghosts were real. Over time it got to the point where I no longer bothered to investigate strange phenomena, because they had become routine.

Finally one day I was literally touched, in a well lit room, by something I couldn’t see. There wasn’t another human anywhere within arm’s reach. The only other person present never left my sight.

Even forty years later, I vividly remember that particular experience, because that raised the bar to a completely new level. Seeing had become believing, but touching kind of freaked me out, because it hadn’t occurred to me it would be possible to feel what I couldn’t see.

Of course, I naturally expect you to remain skeptical about my personal experiences.

But by the same token, I also expect people to understand why I say without fear of embarrassment that I believe ghosts exist — my own repeated personal experiences (which amounts to empirical evidence to me, when collected in the first person) have left me no choice.

It is prudent to remain skeptical of extraordinary claims such as that ghosts exist, and to demand extraordinary evidence to validate them. In fact, there have been a number of sensationalist, bogus ghost stories told by people apparently looking for free publicity, or for whatever reason.

Because I already believe in ghosts and because I know the history of the prison, I wouldn’t dream of sitting in the gas chamber in the New Mexico State Penitentiary at midnight like actor Scott Patterson did — that’s the very prison where the most brutal riot in American history took place in February 1980. Unspeakable horrors took place there.

However, before skeptics like Michael Shermer completely rule out the possibility ghosts exist, they should be willing to honestly investigate claims, not to summarily dismiss them with little or no investigatory effort.

Unfortunately, there is reason to suspect Mr. Shermer might be somewhat selective in the application of his skepticism. He curiously accepts the politically correct arguments for global warming and the theory of evolution with little or no skepticism, yet offers absurd challenges to phenomena that doesn’t fit into his current worldview.

Deep Space photo from the Hubble telescope

In regard to alleged supernatural phenomena, it seems Mr. Shermer employs an impossibly high standard when evaluating alleged scientific evidence he deems questionable.

For example in one televised experiment, Mr. Shermer had been invited to observe experiments involving people who claimed to have psychic abilities.

One alleged psychic in particular appeared to be uncannily accurate in his results, so Mr. Shermer asked to personally test the subject.

In the first test, the psychic had drawn a picture that Mr. Shermer conceded had closely resembled the image in the photograph kept in a sealed envelope.

In the second test, however, rather than using a photograph of an object, or a person, animal, airplane, skyscraper — instead of using any image with a definable shape, Mr. Shermer chose the absurd.

He literally could have used a photograph of anything. Think about it.

Shermer could have used a photograph of a palm tree, a sports car, an airplane, an alligator, or the Statue of Liberty. He could have used Piss Christ. Shermer could have chosen an artist’s rendering of a Tyrannosaurus, Archaeopteryx, an ant, an Apple or an apple.

He even could have tried to trick the alleged psychic by reusing the same photograph from the first test, thinking he’d never suspect it.

But instead Shermer used a photograph of…nothing. He chose the photo of Deep Space taken from the Hubble telescope, shown above.

Naturally, with nothing to visualize, the “alleged” psychic simply drew dots on the page. And to no great surprise, Shermer determined that the psychic’s dots on the paper failed to satisfy his demand for irrefutable proof.

Tough to dispute.

How exactly does one draw a reasonable and accurate picture of outer space? It would appear that Mr. Shermer never had any intention of allowing an alleged psychic to provide evidence which could possibly be construed as legitimate, concocting a ridiculous standard of proof in order to declare the experiment a failure, no matter the result.

Yet when presented with apparently quite credible evidence, rather than seeking to honestly attempt to validate the results, Mr. Sheerer moved the goalposts. Sadly, that makes him worse than just a dishonest skeptic.

Mr. Shermer apparently denies the existence of incredible evidence, no matter how credible it is.

Those dictionary definitions are for “sceptic” not “Skeptic”. The misspelling isn’t by accident.

The modern Skeptic movement is based on taking an evidence based approach to all subjects.

Actually, the definition is the same for both. The word “sceptic”is merely the spelling commonly used in Britain whereas “skeptic” is more commonly used in America.